|

Welcome back to my blag series "Jazz for the Classical Vocalist. This might be a good time to revisit that video in the introduction post. If you would prefer not to be a joke that's posted on social media in perpetuity, read on. So, what's going on here? Can you identify why these poor singers have ended up being shamed for this performance for so many years? In contrast, let's check out the work of the great Carmen McRae, performing live in 1986. How would you describe the difference in the tone production of Carmen McRae in comparison to the singers in the first video? She's mostly staying in a register that classical vocal teachers don't talk about, and it's called "mix." It's not chest voice, and it's definitely not head voice. It rests securely in the front of the mask. This type of vocal production works right in the register that spans the break in the area of E4 and F4. Try singing triads starting on and A3 and going up to an A4 in a super nasal tone using the syllable "nya." You should using much less air than you would in head voice. To understand this, close your lips and blow out against them. Do you feel that pressure building in your core? Then try building pressure behind the syllable "B" and then sing "Bee" around an F4. It should feel bright and highly pressurized in your core.

Homework - Pull out the Latin tune that you chose in blog #2, and try singing it on a bright, nasal "nya" on every note. You can also try singing it on the syllable "bee" to practice building a more pressurized tone. You're at the point now where it might help you to work with someone who specializes in jazz and CCM genres to make sure you're getting this right. I'd be happy to meet up on Zoom to see how you're doing with this, so just let me know!

0 Comments

We already covered a large part of phrasing last week when the focus was on rhythm. Good phrasing definitely locks-in with the rhythmic groove. However, when we're using lyrics we are also telling a story. If you sing the rhythms you see on a lead sheet, you will sound square and inauthentic. One of the things that makes jazz singing so attractive is it's intimacy. If you ever see a truly great singer live, you might feel like they are singing straight to you. One of the ways they do this is by delivering lyrics using rhythms that sound closer to the cadence of spoken language.

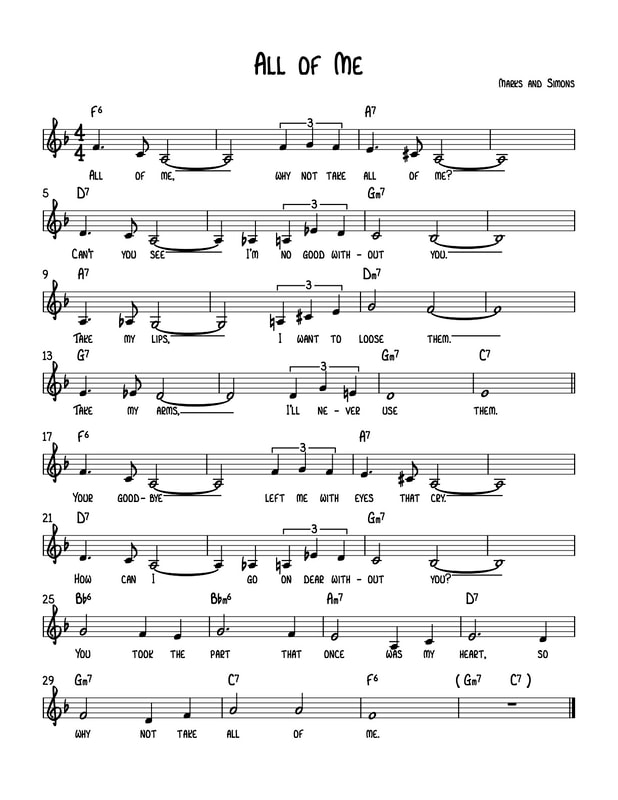

Take my example of “All of Me.” What if you were to sing this melody exactly the way it is written on the lead sheet? It definitely wouldn't swing, but it would also sound very formal and not at all personal and intimate. The answer is to deliver the lyric in a way that not only swings, but also takes on the character of spoken language.

Try reading the lyrics to “All of Me” out loud as if you were speaking to someone sitting next to you. How does your spoken rhythm differ from the notated rhythms on the lead sheet? If you're not sure, try reading the lyrics out loud using the rhythms as notated. One difference you might notice is that when we speak, we don't hold vowels for a long time like we do when we are singing. Also, some words or syllables get more stress than others, and other words or syllables are held a little longer. Your goal is to deliver lyrics in a way that is unique and authentic to you while also enhancing the groove of the music.

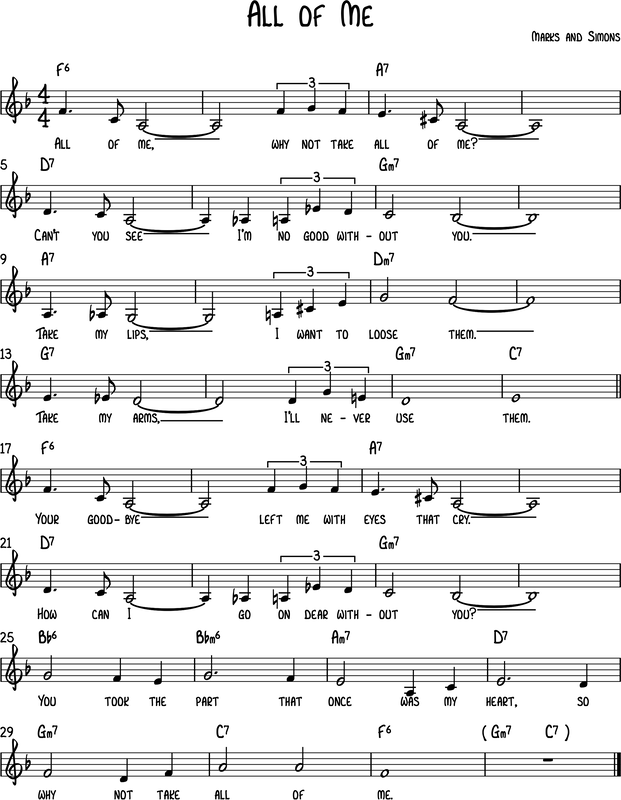

The great pianist and vocalist Shirley Horn was a master at jazz phrasing, especially on ballads. Watch her performance of “Here's to Life” and observe how she's delivering the lyric. She's not making a big deal out of her beautiful voice. She's delivering the lyric in the most honest and intimate way, and she has the audience in the palm of her hand. Homework – Take the Ballad that you chose from my 100 Jazz Standards for Singers list. Start by delivering the lyric like a soliloquy in a play. Dissect each phrase to observe how you say it rhythmically. Sometimes you can anticipate, but in general, you'll find that back-phrasing works well in ballads. In some cases, you may need to adjust to line-up the melody with the chord changes. Practice your ballad using your speech rhythms until it feel quite natural and authentic to you. When in doubt, go back to the Shirley Horn video for inspiration! Most new jazz singers are all excited about improvisation (rightly so) but they think the most important part of improvisation revolves around pitches. Nope! The single most important thing in jazz is rhythm and groove. You can sing all sorts of crazy notes and it won't sound like jazz if you can't groove. So what is “groove?” Our friends at Wikipedia describe “groove” as the sense of an effect ("feel") of changing pattern in a propulsive rhythm or sense of "swing". In jazz, this comes down to syncopation. Rather than give you a long theoretical explanation, let's discover what this means by listening to a really great jazz singer. Since my sample lead sheet was “All of Me,” let's keeps using that song as an example. Here's a clean version without all of my annotations. To do this exercise, you need to find Ella Fitzgerald's version of “All of Me” on a streaming service or YouTube. Listen to Ella's version while you read along with the lead sheet. Pay particular attention to what she's doing rhythmically. Is she following the rhythms as they are written? If not, what is she doing? Can you find a pattern?

If you noticed that she's singing off the beat a lot of the time, you're right on. Most of her phrases begin off the beat and on the beat. On top of that, she often puts a little bit of stress on off-beat notes. For another great example of swing feel, listen to “Splanky” on the Basie band's album titled The Atomic Mr. Basie. Tap your thigh lightly with your hand on the beats while you listen. Note how much attention is paid to off beat rhythms. You will definitely hear and hopefully feel the power of swing rhythms. While you're at it, listen to the whole album – it's one of the swingingest (a new word?) albums of all time. Homework – Take the medium swing tune that you chose from my 100 Standards for Singers list on the Resources page. Sing the song while you lightly tap your hands together. Try beginning each phrase ½ beat early. This is called “anticipation.” Then try singing the song while singing each phrase ½ beat late. This is called “back-phrasing.” Finally, try ending every phrase off the beat while using either anticipation or back-phrasing on the beginning of every phrase. This can be quite challenging for some people, so feel free to sing at a fairly slow tempo like 90 BPM. Welcome back to “Jazz for the Classical Vocalist!” Now that you have chosen some songs and you know your keys, it's time to get some lead sheets together. Some more advanced players you work with will know hundreds of jazz tunes and can play them in most any key. However, it's likely that you'll work with instrumentalists who like to have a lead sheet, especially for tunes you're singing in a non-standard key. If you can notate music very neatly, it's OK if you have hand-written charts. However, I strongly recommend that you learn how to notate music using computer software. The reasons for this are numerous.

There are a number of good programs that run from very expensive to free.

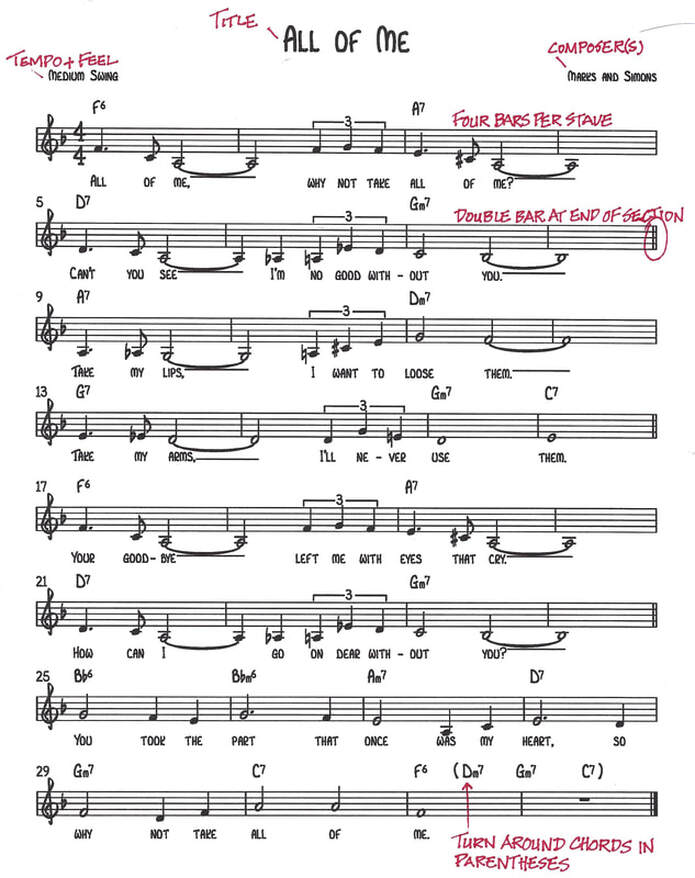

My recommendation is to start with a free program like Musescore and decide later if you need to upgrade. If you're just making lead sheets, you'll probably find that the free programs are just fine. Now, let's talk about what a good lead sheet looks like. Here's a simple lead sheet I made of the standard “All of Me.” It's clear, easy to read, and has just the bare minimum information one needs to get through the tune. (Turn around chords are chords that lead back to the beginning of the tune.)

Homework – Choose one tune from your list of four songs to begin with that needs to be transposed. Create a new lead sheet in your key using my lead sheet of “All of Me” as a template.  Welcome to Blog #3 in my series titled “Jazz for the Classical Vocalist!” So many choices! Now that you have chosen a short list of tunes to begin learning, you will need to figure out the best key for your voice. If there is one mistake that I see classical singers make, it is choosing keys that are way too high. It doesn't matter if you're a coloratura soprano, you'll be singing jazz closer to your speaking register. This performance practice stems from the widespread use of microphones in jazz and popular singing. You don't need to belt out a high note to reach that last row of seats. Your job will be to make those folks in the back feel like you are right there singing to them. This requires singing in a way that has the intimacy of spoken language.

Many jazz standards were originally written for Broadway during an era that the singing style was largely “legit” in the head voice. Therefore, the original keys are uncomfortably high for most female jazz singers, but they often work just fine for males. You'll often find that most standards just need to come down a perfect 4th or 5th to work for most female voices. You'll find that most Latin tunes are already in comfortable singing keys. To find your key, start by finding the lowest note in the song. Then take the key down to the point that the lowest note is towards the bottom of your range when you are fully warmed-up. It's better for your band if you choose a key that is closely related to the original key. If the original key is in Bb, F is a much better key for the band than E. If you can, try to stick with flat keys. Since the most popular wind instruments in jazz are in Bb or Eb, jazz musicians play in flat keys ways more often that sharp keys. Homework – Take the four songs that you chose from my list of 100 Jazz Standards for Singers and figure out the keys that you think are best for your voice. Welcome back! There are many ways to build your repertoire. Traditionally, jazz was shared aurally. Young musicians would learn new tunes from mentors, other musicians and recordings. However, you may not have a large group of jazz musician friends, or you don't have the skillset needed to learn harmony aurally. Since you're a classical vocalist, I'm assuming you can read music, so let's take advantage of that skill. As you progress, your aural skills will improve dramatically.

Most jazz musicians have a large collection of what we call “Real” books or “Fake” books. Even though they are opposite words, they mean the exact same thing when it comes to a collection of songs in a book. These books generally have just the melody, the lyrics and the chord progression on a single page. You're going to need at least one book of tunes to get started, so let's look at what makes a good real book. A good real book is copyright legal. There are a number of books that circulated through the jazz community for many years that were hand-written melodies and chords taken off of recordings. These books had a number of problems. They were notoriously inaccurate, and they were not copyright legal, which meant that the composers and copyright holders never received their fair share. Years later, publishers finally realized that there was a huge demand for accurate, clearly notated jazz standards so they started publishing legal collections of the most popular jazz standards. When I talk about “jazz standards,” I'm referring to a canon of certain compositions. In classical vocal literature, the “canon” includes pieces such as the Italian Songs and Arias, Bach Cantatas, and French art songs. The jazz canon includes standards like “Satin Doll” by Duke Ellington or “Night and Day” by Cole Porter. You'll want to have a variety of different types of songs in your repertoire, with a combination of medium swing tunes, latin tunes, ballads, up-tempo “burners” and contemporary tunes. Resist the urge to build your repertoire around ballads. Consider having songs from two of the other categories to every ballad in your book. Focus on songs that everybody knows and loves, but also consider having a few lesser-known tunes to add interest to your sets. This can also include a couple of originals if you compose. Homework – Go to my Resources page and look through my list of 100 Jazz Standards for Singers. Choose the first few songs you would like to begin with. Choose one medium swing, (8th notes are not equal, and the tempo ranges from 100 to 200 BPM) one up-tempo swing, (tempos above 200 BPM) one ballad, (straight 8th notes, tempo range from 60 to 90 BPM) and one Latin tune (these generally come from Afro-Cuban or Brazilian jazz and have straight 8th notes.) Stay tuned for blog #3 - Figuring out your key. See you soon!

Welcome! My name's Donna Wickham, and I'm a jazz and classical musician who heads the vocal jazz program at the University of Denver Lamont School of Music. Over the years, I've encountered many classically trained singers who wanted to sing jazz, but despite all of their musical training, they just weren't sounding “jazzy.” This YouTube video is a great example of terrific classical singers trying to sing contemporary commercial music.

As you can see, these very accomplished singers are not very effective singing this style of music. If this resonates with you, I hope you'll join me for this series I'm calling “Jazz for the Classical Vocalist.” In this 10-part series, we'll be touching upon some of the techniques and skills you'll need to get off to a good start in your exploration of jazz singing such as Building your repertoire Figuring out your key How to write a basic lead sheet in your key The Importance of Rhythm Jazz Phrasing Jazz Vocal Production Improvisation Working with a Rhythm Section The Next Steps in Your Journey. If singing jazz is an important goal for you, or something you are curious about, make sure to follow along so you don't miss anything. As we go along, feel free to comment about the content or ask questions. See you next week, when we discuss how to begin building a repertoire of jazz standards. |